The rise of online classes after COVID-19: best practices based on literature

Since the coronavirus outbreak, online classes have become the cornerstone of modern higher education. While most universities, colleges or other educational institutions have made the complete transition to online teaching, teachers are still struggling with ways to engage students online. They are required to make tough decisions everyday whether between asynchronous and synchronous learning or educational tools that they need among hundreds of options.

Before the obligatory transition, online courses came in many forms, from Massive Online Open Courses (MOOCs) to single modules or full online bachelor’s and master's degrees being offered online. They had been regularly used in pedagogies like blended learning and flipped classroom. Online classes are now the only option that teachers have to continue teaching. This situation is expected to disrupt education irreversibly but it is still too early to observe the outcomes. Luckily, previous studies have shown a positive relationship between the use of online learning, student engagement and outcomes of learning[1].

Online learning provides opportunities for higher education to deliver services for people continuing their education, to leverage technology to reduce burden on teachers and to use improved pedagogies better suited to maintaining student engagement.

We recommend checking out our ebook on course design in online, hybrid, blended, and hyflex setting – "Quality online teaching and learning: Achieving the higher education we deserve". In this you will find the challenges of online transition, and how to address these with flexible teaching, along with 2 handy frameworks to help you utilize technology in implementing the flipped classroom and team-based learning.

Benefits of online classes delivery

Online classes make education more flexible, which in turn makes higher education more inclusive. Many students, particularly adult students or working students need flexibility in their schedules and module choices in order to access education[2]. Online classes also provide opportunities for students from traditionally marginalized groups. Studies have shown that students who are first in their families to study at university level, people from low socio-economic backgrounds, people of colour and students with disabilities benefit significantly from the availability of online courses[3].

Online classes also appeal to newer generations of students. The widely hailed generation of ‘digital natives’ are now in higher education and are used to having technology as a thread through their everyday lives. Millennials have different expectations of higher education with flexibility, active learning and digital tools being some of them[4]. Online classes appeal to millennials who are comfortable with technology and are used to ingesting large amounts of digitally provided information.

Active learning in online classes

Active learning, which turns away from the tradition of static, unidirectional lectures, uses more interactive forms of learning, including activities such as:

- conceptual mapping

- brainstorming

- collaborative writing

- case-based instruction

- cooperative learning

- role-playing

- simulation

- project-based learning

- peer teaching[5]

Evidence shows that active learning focuses more on understanding and other higher order functions, rather than mere knowledge retention[6]. While not all active learning activities are possible during online classes, many are enhanced by technology. The organization and mass-to-mass communication made possible by technology allows these activities to be better organized and more easily overseen by teachers.

Studies have shown that online classes are particularly helpful for encouraging collaborative learning[7] and that asynchronous interactions between teachers and students helps to engage learners and encourage reflection[8]. Both of these techniques are strongly linked to active learning principles.

Challenges of online classes

Online classes, whether fully online or as a part of more traditional teaching methods do have stumbling blocks. It is feared that the obligatory transition to online classes may cause lower enrollment rates in universities and colleges except the ones in Ivy League. Earlier studies show lower completion rate for online classes compared to face-to-face teaching, although there is a lack of evidence concerning blended learning courses which combine both styles of teaching[9].

Technical difficulties are a barrier to the use of online courses. Both students and teachers are frustrated with complications, and these difficulties can lead to students engaging less with the courses. Instructors must often devote time to fixing technical issues[10] and editing content can become a complex and arduous task[16].

Online modules can alienate some students, just as they include others. Blended or online learning asks that students take more responsibility for their learning, transforming them from passive to active learners. However, this can be a challenge for some students, particularly those more used to passive learning in school. These students may need more motivation, organization and discipline to be able to be successful[11].

Lastly, accessibility of online courses is a major problem with full-online learning. The availability of working internet connection, electronic devices such as laptop or mobile phones or even existence of a suitable learning environment changes from student to student. The rushed transition to online teaching can also create difficulties for disabled students.

How to improve online course delivery

Several methods for improving online classes delivery have emerged. Obvious problems such as poor integration, lack of skills or technical malfunctions must be addressed first.

Digital specific course design

Online classes need to be designed specifically for digital devices, rather than merely transferring offline content to a digital format. Lazy course design ends up creating a disengaging experience for students[12]. Teachers in a recent study of Australian universities noted specifically that lecture content merely converted to video format was not enough to engage their students[13]. To tackle this problem, teachers can use tools such as Interactive Video to make their online lectures more engaging.

Utilize face-to-face interactions when possible

One of the biggest problems with online classes is poor retention rates. However if online classes are carefully combined with face-to-face interactions, retention rates are more likely to improve. Face-to-face contact does not necessarily have to involve teaching, but can include support from teachers in the form of video call whether they use Skype or Zoom. Studies show that students, particularly millennial students need a sense of being cared about by their professors and that this feeling can dramatically improve their motivation[14].

Supported engagement is crucial

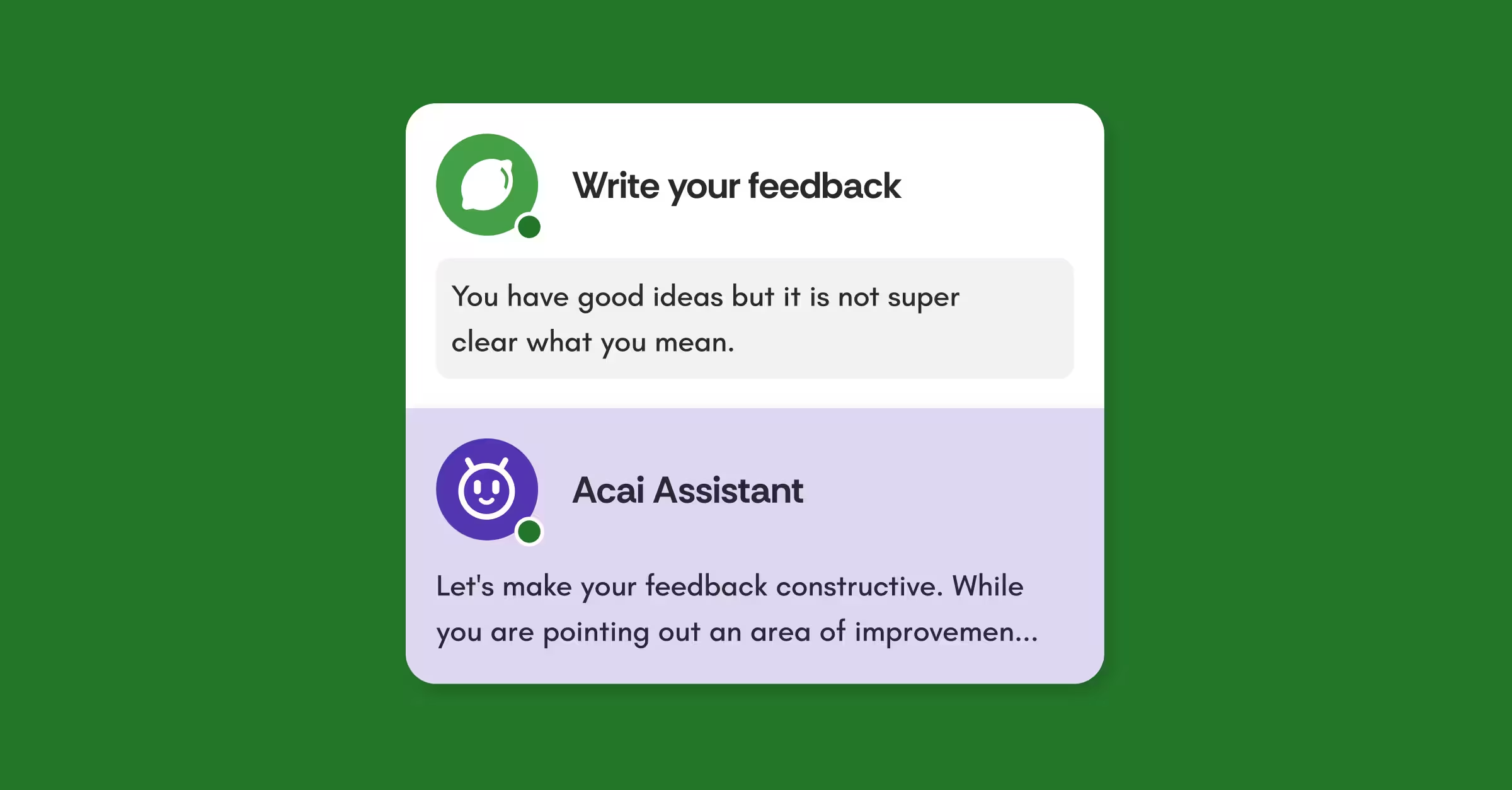

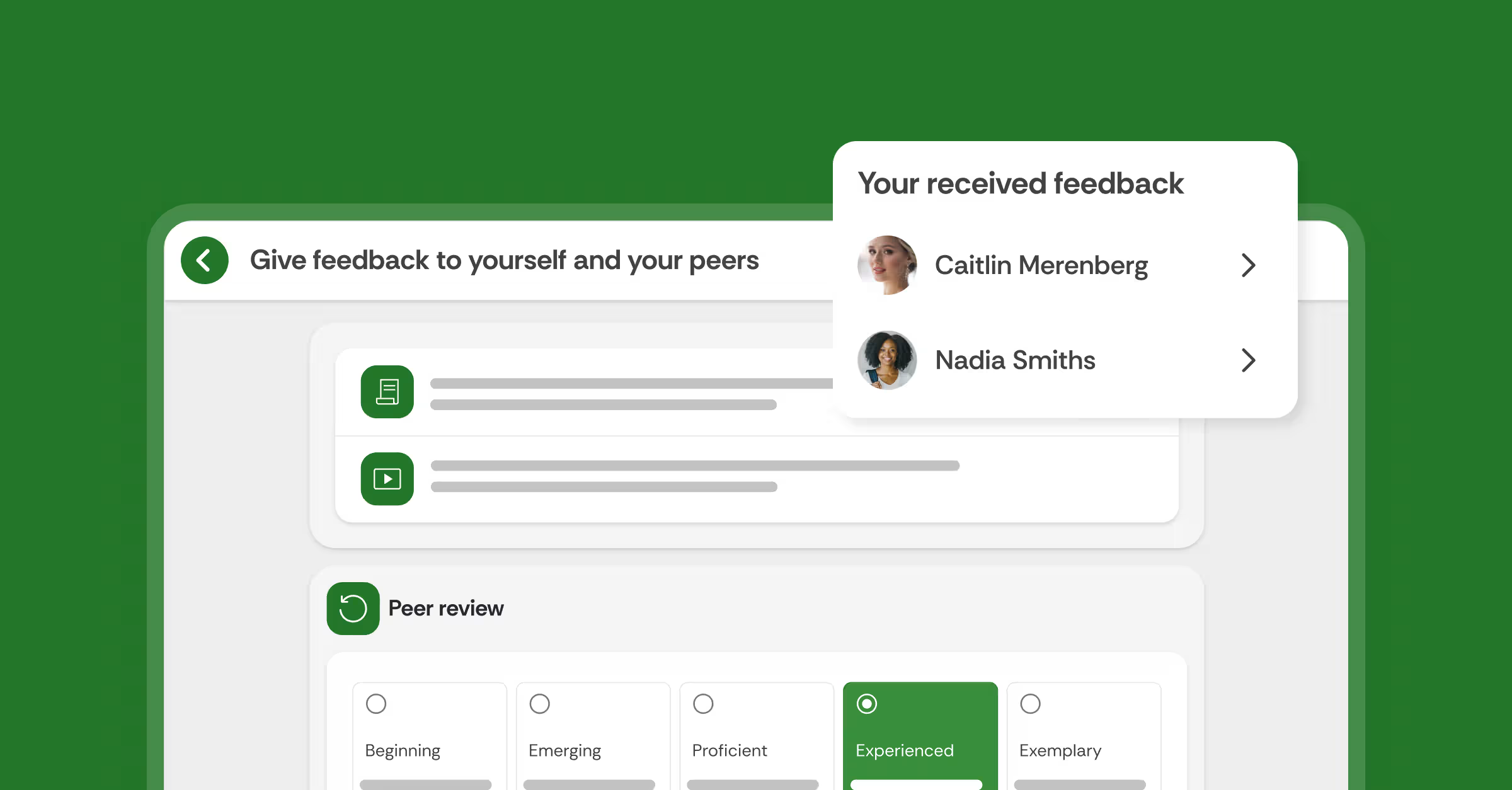

In general, regular and constructive communication between students and teachers improves the online learning experience. It is often referred to as supported engagement. In fact, a recent study determined that ‘the quality and timeliness of lecturer feedback was the most valued form of learning connection identified by students’[15]. The feedback loop which is automatically present in face-to-face interactions needs to be considered in online course delivery. Teachers can use educational tools such as Assignment Review or they can deliver their feedback in the form of discussion response, regular formative assessment and group activities such as wikis or forums.

Set clear expectations for learning

Some students struggle with online classes as they are more used to a more intimate style of teaching. It is important for teachers to set clear expectations for their students. Many students will have no prior experience of managing their own learning experience. This disconnection can be even stronger with online classes. Expectations such as requiring students to submit regular formative assessments can be helpful in directing students' energies.

Conclusion

Online learning is a complex and emerging field. There are both challenges and benefits to the use of digital technologies, either as stand alone courses or as integrated with traditional course delivery methods. However in order for online learning to be successful it is clear that the mindset of teaching must change. Educators need to shift from 'a teaching-centred paradigm toward a learning-centered paradigm'[16], in order to appeal to new students and maintain a critical technological edge in a competitive marketplace.

References

[1] Kahn, P., Everington, L., Kelm, K., Reid, I. & Watkins, F., (2017) ‘Understanding student engagement in online learning environments: the role of reflexivity’, Education Technology Research Development 65: 203-218, p.204.

[2] Moore, C. & Greenland, S. (2017) ‘Employment-driven online student attrition and the assessment policy divide: An Australian open-access higher education perspective’, Journal of Open, Flexible and Distance Learning 21(1): 52-62.

[3] Stone, Cathy (2019) ‘Online learning in Australian higher education: Opportunities, challenges and transformations’, Student Success 10(2): 1-11, p.2.

[4] Loveland, E. (2017) ‘Instant generation’, Journal of College Admission 234: 34-38.

[5] Zayapragassarazan, Z., & Kumar, S. (2012) ‘Active learning methods’, NTTC Bulletin 19(1): 3-5.

[6] Ritchhart, R., Church, M., & Morrison, K. (2011) Making thinking visible: How to promote engagement, understanding, and independence for all learners, San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, pp.7.

[7] Dumford & Miller (2018); Thurmond, V., & Wambach, K. (2004). Understanding interactions in distance education: A review of the literature. International Journal of Instructional Technology & Distance Learning, 1, 9–33. Source

[8] Kahn et al. (2017); Robinson, C.C. & Hullinger, H. (2008) ‘New benchmarks in higher education: Student engagement in online learning’, Journal of Education for Business 84(2): 101-109.

[9] Stone (2019), p.2.

[10] Dumford & Miller (2018), pp.453.

[11] Jacob, S., & Radhai, S. (2016). Trends in ICT e-learning: Challenges and expectations. International Journal of Innovative Research & Development, 5(2), 196–201.

[12] Devlin, M. (2013). eLearning Vision. Federation University.

[13] Stone (2019) pp.6.

[14] Miller, A.C. & Mills, B. (2019) ‘If They Don’t Care, I Don’t Care’: Millennial and Generation Z Students and the Impact of Faculty Caring’, Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 19(4): 78-89.

[15] Ragusa, A. T., & Crampton, A. (2018). Sense of connection, identity and academic success in distance education: Sociologically exploring online learning environments. Rural Society, 27(2): 125-142, pp.15.

[16] Roehl, A., Reddy, S.L. & Shannon, G.J. (2013) ‘The Flipped Classroom: An opportunity to engage millennial students through active learning strategies’, Journal of Family & Consumer Sciences 105(2): 44-49.

![[New] Competency-Based Assessment](https://no-cache.hubspot.com/cta/default/3782716/interactive-146849337207.png)